The Guess Worker

Hope

Overview:

- Optimistic thoughts lead to an increase in pleasure and a decrease in pain

- This might be due to a rerouting of impulses from "down" to "up" dopamine neurons

- The rerouting may occur because of a strengthening of certain synapses

- This strengthening could be initiated when two neurons simultaneously receive frequent impulses

Optimism is good for you. People who are more positive about the problems they face are more likely to overcome them. In general they are also more healthy, both mentally and physically.*1 So why doesn't everyone choose to be optimistic? Because, of course, it's not so simple. Some people, no matter what they do, always seem to be pessimists. Optimism is very much like a talent: if you have it naturally, you are lucky; if you don't, it isn't easy to develop.

The pleasure of optimism

So what is optimism and why do only some people have it?

Let's imagine that you have hit bad times. If you are a optimist you will focus on the future, on a time when things hopefully will be better. You might say to yourself something like: "I will get out of this somehow" or "I will succeed eventually" or "I will get what I want in the end."*2

What do these kinds of thoughts have in common? The first thing we can say about them is that they are pleasurable. If you say to yourself "I will succeed", you feel good - especially if you are sure of it.

Pleasure, in my book, must mean rises in dopamine levels. How might these rises come about? A thought is a concept and the concrete form of a concept is likely to be found in the neurons and synapses of the brain. If "I will succeed" gives pleasure, the neurons of this concept must be connected to "up" dopaminergic neurons. *3

Dopamine soup?

So the firing of the neurons of an optimistic concept leads to the firing of dopaminergic neurons, which in turn leads to an increase of dopamine and the feeling of pleasure. At first glance this seems to explain how optimism works: if life is bad, a bit of pleasure is going to make you feel better. In reality, however, the picture must be more complicated. Optimism doesn't only give pleasure – it also reduces pain. If you lose your job, the thought that soon you are going to get another one gives you pleasure. But that same thought also takes some of the sting out of the dismissal. Somehow our feelings affect each other.*4

But how? I can think of two possible mechanisms. The first is the least likely. Here the brain is bathed in a dopamine soup. Dopamine is added to the soup when something pleasurable is experienced and dopamine is removed from the soup when something painful is experienced. When both painful and pleasurable stimuli occur at around the same time, how good or bad you feel depends on the balance between the rises and the falls of dopamine. The main problem with this idea is that the brain wouldn't easily be able to tell which stimuli are pleasurable and which painful: all the dopamine is mixed up into the same soup.

A finely tuned mechanism

The second mechanism is more finely tuned. It is also more complex and so to illustrate it I'll use an example which could be true to life.

The small plane you are travelling in has crashed in bad weather in a remote part of the High Andes. You are not seriously hurt but all the other people on board are killed. No one knows exactly where you are, the cockpit radio isn't working, it is freezing cold and you only have enough food for two or three days.

Immediately after the crash your mind forms what could be called concepts of situation. These concepts are not in themselves painful – based on incoming information from your senses they merely make you understand what has happened.

Fairly soon, though, you begin to have negative thoughts: will anyone think of looking for you? And if they do, will they find you before you die of exposure, illness or starvation? You think about perishing in the wilderness and about how you might not see the people you love ever again. We could call these thoughts collectively concepts of doom. They are connected to "down" dopaminergic neurons which makes them painful.

Not all is hopeless, though, and you could have some positive thoughts too. A search party might be sent out to look for you soon and with a bit of luck you could be rescued. We could call such thoughts concepts of rescue and they are connected to "up" dopaminergic neurons which makes them pleasurable.

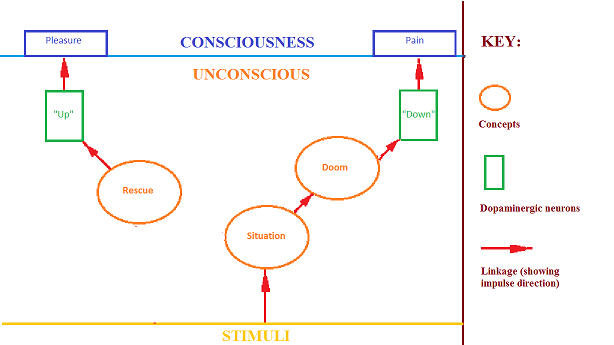

Not surpringly at the beginning you have very few - if any - of these positive thoughts. That is because concepts of rescue are not linked, or are only weakly linked, to concepts of situation. Instead, there is a strong linkage between concepts of doom and concepts of situation. Nerve impulses arriving at situation move unhindered up to doom and then on to dopaminergic neurons resulting in painful feelings. This pathway is shown in the following diagram:

"

"

The route to pleasure

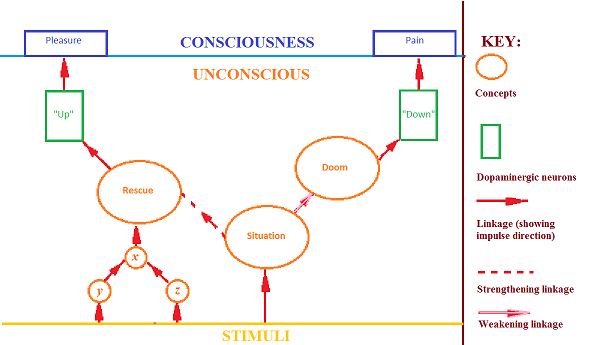

You are, however, a steadfast optimist and never feel down for long, even in the worst circumstances. Your negative thoughts quickly turn to positive ones. How might this come about? Suppose a linkage between situation and rescue forms and strengthens and at the same time the linkage between situation and doom weakens. As a result more of the impulses arriving at situation are diverted away from doom and pass up towards rescue. That would mean that "down" dopaminergic neurons are fired less and "up" dopaminergic neurons more, leading to less pain and more pleasure. The diagram below illustrates this idea:

"

"

How to get stronger

So far, so good - perhaps. But there is an obvious hitch in the hypothesis: why would the linkage between situation and rescue get stronger? What does getting stronger mean anyway?

It makes sense to assume such linkages are made up of synapses. If so, strengthening a linkage could mean either forming more synapses or making existing synapses work more efficiently. How exactly this happens is not relevant at this stage: what is relevant is why the strengthening occurs.

My guess is that linkages between concepts become stronger the more often the concepts are activated at the same time.*5 Or to put it in physiological terms: the more often two neurons receive impulses simultaneously, the more the synapses between them are strengthened.*6

Let's go back to the last diagram above. How often will situation and rescue receive impulses? For situation the answer is: "very frequently". The stimuli of your circumstances are around you all the time and are almost constantly firing the neurons which make you understand what has happened.

But what about rescue? Here the answer is: "It depends on how you think".

The God factor

Imagine you have a strong belief that God will help you. You are convinced that through divine intervention in a short time a search party will find you. We might say that the conviction that God helps you supports the idea of being rescued.

In this context the word support probably means there is a strong synaptic linkage between the concepts God will help me and rescue. Suppose God will help me is x on the diagram above. Because of the strong linkage between x and rescue most of the impulses arriving at x will reach rescue. So if there are many impulses at x there also will be many impulses at rescue. With both rescue and situation receiving a lot of impulses simultaneously, the linkage between them will strengthen.

But what if you have doubts about whether you deserve to be rescued? You believe in God but think He might not help you because you have sinned. We could say these doubts undermine your belief that God will help you.

In this context the word undermine probably means there is a weak or weakening synaptic linkage between the concepts deserving and God will help me. Suppose the concept of deserving is y is on the diagram. Because of the weak linkage between x and y, only a few of the impulses arriving at y reach rescue. With only situation (and not rescue) receiving a lot of impulses, a strong linkage between them will not be made.

Now the evidence

Of course you don't have to be religious to be optimistic, but it helps - especially when things look really bad. If you don't believe in God at all, you won't have any chance of boosting the impulses at rescue through the pathway described above. But they might be boosted through an alternative route. Suppose you see planes on the horizon. Then you see them circling as if they were searching. They seem to be getting closer...

We might call such observations evidence because the concepts formed from them are not many layers away from the sensory information received. These concepts could fill the spaces x, y and z vacated through scepticism about God. The more evidence there is, the more impulses will reach x, y and z and the stronger the linkages will be on the left side of the diagram. When you finally see a plane fly directly overhead, and the pilot tilts the wings to let you know you have been spotted, the linkage between situation and rescue is very strong. Now you know you will be rescued and you feel fantastic.

New linkages to behaviour

In the above example bad feelings have been changed into good feelings by the creation of new linkages. The mechanism described might explain much about how humans think and behave. Turning bad feelings into good is the aim of psychotherapy and it tries to do it by stimulating underused neural pathways. And this stimulation leads to new, happier, linkages. Acquired tastes – things thought previously to be disgusting becoming enjoyable – also probably come about by the formation of new linkages. It could also explain how humans are able to suppress or emphasise some wants in favour of others – and in this way give the illusion of having free will. Similarly it could explain a whole lot about our cultural and social behaviour – because this is all about acquired tastes and suppressing or emphasising wants.

However, before I explore any of these ideas in further posts, I want to understand more about how these new linkages are formed. In the example there is pain, then a new linkage and then pleasure. That is the same sequence of events whenever we solve any problem. It's true for solving a crossword puzzle clue or for finding a way to pay the mortgage. Understanding why this sequence occurs could be the key to understanding how we think. And, of course, we need to understand how we think before we can understand properly psychotherapy, acquired tastes, free will (or the lack of it) and cultural and social behaviour.

*1. Numerous studies have show the health benefits of being optimistic. Some of these are mentioned in this article from The Guardian newspaper: www.theguardian.com/science/blog/2009/aug/11/optimism-health-heart-disease

*2. There is another kind of positive thinking. Instead of thinking about the future you might say to yourself something like: "It could be worse" or "Life's not that bad" or "There are plenty of things I can still enjoy". Having this philosophy could mean your remaining relatively cheerful even if things never improve. Strictly speaking though, this is not optimism because you are concentrating on the present.

It could be that a thought such as "It could be worse" makes you feel pleasure in the same way as relief does. (See The dynamics of pain.) Pain is felt when imagining worse circumstances than the ones you are actually experiencing. That means dopamine levels are pushed down. But the dopamine levels quickly rise again (ie. giving the feeling of pleasure) as soon as you confirm to yourself that the worse circumstances aren't actually happening.

*3. When "up" dopaminergic neurons are fired, dopamine is released into their synapses. When "down" dopaminergic neurons are fired, dopamine concentration in their synapses decrease. For more on this see The dynamics of pain.

*4. We all experience this in various ways, in different situations. If you are in love, you don't care two hoots about how rude the shop assistant was to you in the morning. In another frame of mind, though, it'll spoil you day and might make you unnecessarily rude to others. If you are depressed, activities you once found enjoyable no longer seem to give any pleasure. On the other hand if you are feeling slightly down, doing something you really enjoy might be enough to put you in a better mood.

*5. To avoid clutter I haven't explored why linkages become weaker. The reason, I guess, is simply the opposite of why linkages get stronger: if two concepts are rarely activated at the same time, the weaker the linkage between them becomes.

*6. There are good reasons for believing that frequent impulses arriving simultaneously at two neurons cause a strengthening of synapses between them. One of these reasons is entirely theoretical: if two events consistently occur at around the same time there is likely to be a causal link between them. Our brains have been evolved to connect such events together. For more on this see The concept.

Comments powered by CComment