The Guess Worker

Depression

Overview:

- Depression is caused by persistent pain

- Persistent pain pushes dopamine levels down to a new equilibrium

- Depression consists of two stages

- The first stage is a painful state where dopamine levels are falling

- The second stage is an unmotivated state where dopamine levels are stable

Depression is a paradox: it is painful and at the same time it brings about a loss of motivation. This combination of feelings ought not to happen. Pain is biology's way of motivating and so the pain of depression should mean more motivation and not less. What, then, is going on during depression?

What causes depression?

Let's start by thinking about what can cause depression. It might be amongst other things: relationship problems, job loss, bereavement, bankruptcy, repossession of one's home, imprisonment, solitary confinement, disabling injury, discovery of a terminal illness or chronic pain. Of these only chronic pain could be considered entirely physical. The rest might be called "emotional".*1 All of them, though, involve some kind of adversity. In one way or another they are all painful.

Of course, pain doesn't always cause depression. Few people get depressed when they stub their toes or burn their dinner in the oven. What is different about the pain which sets off depression? The answer is that from this kind of pain there is no escape – or, at least, that's how it feels at the time to the person experiencing it. It is persistent, long-term pain which won't go away, no matter what the person does. Clearly, it doesn't matter whether the pain is physical or emotional.

Dopamine and persistent pain

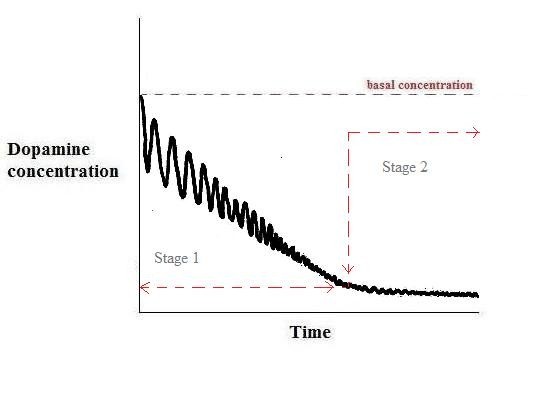

What happens to the dopamine levels of someone affected by persistent pain? As with any pain, dopamine levels in the brain are pushed down below the basal concentration. If the pain signals were to stop, we would expect dopamine levels to rise again and provide relief. In this case, though, the signals don't stop. The dopamine levels can't rise and - if we assume that the signals are frequent and constant – they will instead continue to decrease. After some time, however, they will stabilise at a fixed concentration below the basal concentration.*2 Graphically expressed, this change in dopamine over time looks something like this:

"

"

As can be seen from the graph, we can divide the time from the onset of pain into two stages: the first, when dopamine levels are decreasing overall; and the second, where dopamine levels stay constant.

The two stages of depression

I believe these two stages correspond to pain and loss of motivation respectively - the two states of mind in depression. Why did I just write two states of mind? Isn't depression a single state of mind? After all, we think of it as one mood and call it by one name. But I would guess that a mistake of definition has been made, and this mistake is the reason for the apparent paradox mentioned in the first paragraph. Pain can't happen at exactly the same time as a loss of motivation. However in depression these two states do occur at around the same time and this makes them seem as if they are one state.

So the first stage (when dopamine is falling) is the painful state, and the second stage (when dopamine flattens out) is the unmotivated state. Why, though, does a low but steady concentration of dopamine mean a loss of motivation? As I have suggested in previous posts, rises and falls in dopamine cause feelings of pleasure and pain, and these feelings are necessary for motivation. When the rises and falls can't happen there can't be any motivation.*3

The symptoms

Are these two stages responsible for all the symptoms of depression? Yes - probably. Below are the symptoms of depression, arranged into groups according to the stage to which I think they belong*4:

Group A. Stage 1 only (painful state):

- sadness

- suicidal feelings

- guilty feelings

- irritability

- anxiety

- digestive problems

- aches and pains

- overeating

- insomnia

- restlessness

Group B. Stage 2 only (unmotivated state):

- inability to concentrate

- poor recall

- indecisiveness

- loss of interest in activities which were previously pleasurable

- loss of appetite

- excessive sleeping

- loss of energy

Group C. Both stages 1 and 2:

- feeling of emptiness

- feeling of worthlessness

- feeling of helplessness

- feeling of hopelessness

- fatigue

Can I justify the groupings above? I'm going to look at each group in turn to try to explain the symptoms in terms of the two stages of depression.

Group A

Anxiety, irritability, aches and pains, digestive problems and sadness are all painful conditions, and so it is obvious they belong in stage 1, the painful state.

Why, though, have I included in group A overeating, insomnia, and restlessness which, even if inconvenient, don't seem too painful in themselves? The answer: where there is pain, there is motivation and where there is unstoppable pain there is superfluous motivation. Superfluous motivation means not only that the motivation is excessive but that it also fails to remove the pain causing the motivation in the first place. Superfluous motivation results in overeating, insomnia and restlessness. Sufferers can't stop themselves eating, they stay awake at night worrying and during the day they fret around the house without getting anything done. None of which makes them feel any better.

Superfluous motivation also may be responsible for some of the other symptoms in stage 1. Aches, pains and digestive problems could come from muscles, joints, stomach and other parts of the body working unnecessarily hard.

Anxiety can be seen as the mental equivalent of these physical problems: the mind harms itself in an attempt to free itself from pain.

Group B

Interestingly, some of the symptoms in group B are the opposite of those in group A:

- loss of appetite (versus overeating),

- excessive sleeping (versus insomnia),

- loss of energy (versus restlessness).

The reason, of course, is the loss of motivation in stage 2. Appetite depends on rises and falls of dopamine, giving the pleasures and pains (that is, wanting) of food. When these rises and falls are limited there is a loss of appetite. (This also explains the general loss of interest in activities which were once pleasurable.)

Excessive sleeping and loss of energy undoubtedly are signs of a lack of motivation. It is worth, though, spending a few thoughts on why motivation and energy are connected. Falls in dopamine seem to trigger (through an unknown metabolic pathway) a release of energy to the body and the brain. There is a good reason for this: the body and the brain need energy to try to get rid of painful stimuli. Conversely, when falls in dopamine are restricted – as they are in stage 2 – less energy than usual is supplied. This loss of energy is felt as lethargy and sleepiness.

What about the inability to concentrate, poor recall, and indecisiveness? Together these symptoms mean a reduced capacity for thinking. Why would a loss of motivation affect thinking? As I argued in Thinking, we need to be motivated to think. We think about what is important or what is interesting to us. In other words, we think about things that give us pain and pleasure. When rises and falls of dopamine are limited as in stage 2, concentrating, remembering and making decisions become difficult.

Group C

The symptoms in group C are supposed to belong to both stage 1) and 2). This looks like a cop out. Am I trying to fudge the fact that the two stage theory of depression doesn't make sense? I don't think so. My hunch is that each symptom actually consists of two feelings, each of which belongs to different stage.

I'm going to look at two of the symptoms – fatigue and the feeling of hopelessness. The rest of the symptoms in this group come about in a similar way to the feeling of hopelessness.

Fatigue is a kind of tiredness which feels painful. When is and when isn't tiredness painful? For me, it isn't painful if I lie down and go to sleep. If is painful, though, if I try to resist it by staying awake. My brain tells me that it hurts to try to generate energy when I have very little of it. That's for a good reason: I'm supposed to go to sleep. I imagine the same sort of thing is happening in depression: people trying to get on with their lives are having to battle with their own lack of energy, and that is a painful thing to do. Here, unfortunately, the easy option of going to sleep doesn't resolve the pain which caused the depression in the first place.

We have, then, two feelings – tiredness and the pain from resisting tiredness. Tiredness is the low energy state with low motivation, belonging in stage 2. The pain from resisting tiredness belongs in stage 1.* 5

The feeling of hopeless also is made up of two feelings, even though, as with fatigue, we might not realise it. Hopelessness in the context of depression is assumed to be painful. But actually hopelessness isn't painful in all situations. I may feel, for example, that it is hopeless that I would ever win Wimbledon. But it doesn't bother me.

The implication here is that hopelessness is one feeling and that feeling bad about hopelessness is another feeling. If that's true then hopelessness is an unmotivated state belonging in stage 2 and the bad feeling about hopelessness is a painful state belonging in stage 1.

Feelings affect each other

So it seems that the two stages can explain a lot about depression. They don't explain everything, though. Hopelessness is a case in point. Hopelessness affects other feelings we have in a negative way. How does it do this? Hope, in contrast, is a lifeline which people use to pull themselves out of depression. It affects other feelings in a positive way. What is hope and why does it affect other feelings? I will, I hope, answer these - and other - questions in the next post.

* 1. Of course, disabling injury and terminal illness are physical disorders, but it is usually the emotional reaction of individuals to their disorders which precipitates depression.

* 2. The reason for dopamine levels stabilising in this way has to do with Le Chatelier's principle. How this law of equilibria affects dopamine levels was discussed in detail in the previous two posts. In The dynamics of pain I argued that pain signals arriving at the synapse lowered dopamine levels. Subsequent signals will lower the levels even further but as the signals keep on coming the amount of decrease becomes less, until eventually there is no decrease at all. When this happens the dopamine concentration might be very low - but it never reaches zero. It reaches a new equilibrium point where the rate of removal of dopamine (which was increased by the incoming impulses) again equals the rate of production of dopamine (which becomes increased because of the lowered concentration of dopamine).

* 3. It isn't a coincidence that dopamine depleted rats (mentioned in Dopamine) also lack motivation. These rats have very low concentrations of dopamine in their brains and for this reason they too can have only limited rises and falls.

* 4. These symptoms have been taken from Wikipedia's article on depression.

* 5. Some readers might wonder why here stage 1 comes after stage 2. Shouldn't stage 2 be the final stage of depression, as it is in the graph? Not necessarily. The graph assumes that the pain signals are frequent and constant. In real life that won't always be true. There may be some relief during stage 2, meaning that dopamine can rise again. That relief can always be pushed back down again if the pain signals resume – causing the return of stage 1. What we should also remember is that although dopamine levels are low in stage 2, they might be pushed even further down if even more intense pain signals are received. That might mean another stage 1, which in turn could be followed by another stage 2 with even lower dopamine levels than before.

Comments powered by CComment