Serious and Sillier

Overview:

- A simple linkage explains how one stimulus affects the feelings of another

- In a concept each of the two stimuli is linked to the feelings of the other

- If a linkage is weak, a second stimulus can only enhance the feelings of the first

- If the linkage is strong, the second stimulus alone can evoke the feelings of the first

Pain makes some pleasures more pleasurable. Food is tastier if you are hungry. Sex is more enjoyable after a long period of unwilling abstinence. And the photos in the holiday brochure look very appealing when the pressures of work start to get to you. Somehow pain intensifies pleasure. But how?

A partial answer

Part of the answer lies with dopamine. Activated dopaminergic neurons release dopamine into their synapses and the resulting rises in dopamine are interpreted by consciousness as pleasure. However, as the neurons are activated repeatedly, the rises of dopamine become less steep. This means stimuli feel less pleasurable the more we experience them. So the first chocolate eclair you eat is tastier than the second and the second will be tastier than the third. *1

Dopamine can explain how a single stimulus becomes less attractive with repetition and, conversely, how it becomes more attractive the rarer it is. What it can't explain, though, is how one stimulus heightens the pleasure of another.

How could low glucose levels in your blood make the food on your tongue more delicious? The neurons of the two stimuli must be connected to each other, but how could this connection increase the pleasure given by the food?

A simple solution explains a lot.....

Let's imagine the most straightforward connection possible - a branch from one neuron linking up to the other neuron - and see if this could produce the desired effect:

"

"

Suprisingly this simple linkage can explain a lot. Suppose you're hungry and have something to eat. Impulses will be sent from taste receptors in your mouth and, at the same time, from glucose receptors for hunger as well. Some of the impulses from the glucose receptors will be diverted along the branch towards the up-dopaminergic neuron for taste. *2 The up-dopaminergic neuron is therefore receiving impulses from two stimuli at once. Obviously it's getting more impulses than it would from a sole source. More impulses mean steeper rises of dopamine and that in turn means more pleasure. In other words, hunger is making your snack more pleasurable.

For one situation, however, the diagram doesn't seem to work: what if you felt hungry but couldn't find anything to eat? Even though your taste receptors aren't sending any signals, the up-dopaminergic neuron is still receiving impulses from the hunger stimulus. This should mean although you aren't eating anything, you would taste something - which, of course, is not something that usually happens.

Possibly the explanation is that the impulses from hunger by themselves aren't enough. Maybe too few reach the down-dopaminergic synapse to cause big enough or steep enough rises of dopamine – and these small rises aren't appreciated by the consciousness. The most the hunger impulses can do is steepen rises already made by taste impulses. In other words: hunger impulses alone are too weak to have an effect; only together with taste impulses can they have an impact on the feeling of taste.*3

….but must be modified slightly

Although the diagram above manages to explain how hunger increases the pleasure of food, it still needs to be modified. That's because in reality the linkages go probably both ways: not only is the hunger neuron connected to the up-dopaminergic neuron, the taste neuron is also connected to the down-dopaminergic neuron. We could represent this bi-directional connection like this:

"

"

According to this diagram not only can hunger increase the pleasure of taste but taste can also increase the pain of hunger. So when you're peckish, a bite of something good might make you feel even more peckish - and that will motivate you even more to take another bite.*4 Just as before, though, the impulses from taste by themselves aren't enough to cause hunger: impulses have to come from both hunger and taste at the same time for a noticeable change to happen.

Depicting a concept

The above diagram could be said to depict a concept because it shows the linking of two sets of information.*5 My guess is that all concepts have the same circuitry. Pared down to the minimal unit, a generalised concept looks like this:

"

"

Concepts probably only differ from each other physiologically in a handful of ways. The dopaminergic neurons can be connected in three combinations: two ups, two downs or one up and one down. That means the linking of either two pleasurable stimuli, two painful stimuli or one pleasurable and one painful stimuli. Another difference between concepts is in the strength of the linkages in them. Linkages can be strong or weak and all degrees in between. Importantly too, the linkages in each direction can be of different strengths.

Responses depend on strength

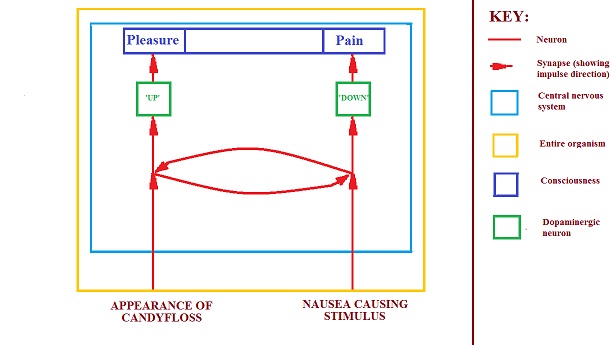

How we respond to stimuli depends on these strengths. Whenever I see candyfloss I always feel slightly sick. It wasn't always like this: I loved the stuff when I was a child. Then, when I was around ten years old, I ate so much at a fair that in the end I vomitted. I suppose that was the moment the strength of my neuronal connections was altered. I developed a strong linkage between the neurons which connected the appearance of candyfloss to the feeling of nausea. From that time on the impulses from this particular stimulus would be diverted away from up-dopaminergic neurons, which had previously given me pleasure, to down-dopaminergic neurons, which would now give me pain. We can illustrate the diversion as follows:

"

"

Even though this concept looks much the same as the hunger-taste concept, there must be a difference in the strengths of the linkages in them. The linkage from taste to hunger can't be strong, because taste by itself doesn't cause the feeling of hunger. In contrast in my brain the linkage from the appearance of candyfloss to the feeling of nausea must be strong because candyfloss by itself can cause the the feeling of nausea.*7

The consequences in our behaviour

Nearly all of human behaviour is dictated by concepts. It is probably very rare that a single stimulus provokes a response in us without this stimulus being linked by concepts to other stimuli. These other stimuli enhance or diminish the pain or pleasure felt by the stimulus so that our behaviour is subtly tailored to meet our needs. Food, sex and holidays become more enjoyable when we don't get enough of them, and that means that we pursue them more vigorously.

Concepts affect our behaviour in a different way when the linkages are strong. Here a stimulus doesn't enhance the feeling caused by another; it evokes the feeling all by itself. So the sight of candyfloss alone is enough to stop me from eating it. When the linkages are strong, the responses can seem unrelated to the stimuli which caused them. The result is our most unpredictable and enigmatic behaviours. Strong linkages can explain our obsessions and sexual fetishes, and why a single word can make a person inexplicably explode with rage, and why in some people the pain of low self esteem is transformed into the pleasure of cruelty.

Not only do the strengths of linkages in our brains dictate how we behave, they also dictate how we think. Thoughts are concepts and physiologically must be the same as any other kind of concept. How much pleasure or pain a thought gives you depends on the strength of the linkages connected to it. That pain or pleasure will determine how you will link up that thought to another – and so ultimately will determine your train of thought. We don't need big leaps of logic to take us from trains of thought to belief systems, moral values and culture.

Touching the surface

The last two paragraphs have touched on many ideas which need considerable development. I hope to explore them all in later posts. Before I get that far, though, I have to understand better the mechanisms our brains use to make concepts. In this post I have looked at linkages which are already there. In the next I will look at memory and how linkages form and break down.

*1. See The dynamics of pleasure for a more detailed description.

*2. For an explanation of up- and down-dopaminergic neurons see The dynamics of pain.

*3. An internet search revealed that when fasting some people dream they taste food. This suggests that the impulses from the hunger stimulus can alone cause the sensation of taste during severe deprivation. Presumably in these circumstances the impulses from hunger are frequent enough to cause appreciable rises in dopamine.

Interestingly there are many more reports of seeing food in dreams. It seems that hunger is more strongly connected to our visual neurons than it is to our taste neurons. The reason could have something to do with the pre-eminence vision has over the other senses in humans.

Dreams of seeing or tasting food are, of course, illusions. So perhaps the diagram can give us a clue as to how illusions, dreams, hallucinations, imagination as well as memory come about. This is a subject for future posts.

*4. Once again, similar experiences happen more often with vision than taste. (See *3 above.) More usually than a chocolate eclair's taste, the sight of it gives you a sudden pang which makes you want to eat it.

*5. For my definition of a concept, and a discussion of this definition, see The concept.

*6. The linkage in the opposite direction must be weak because the stimuli which cause nausea certainly never give me pleasure

Comments powered by CComment